Study Finds Significant Mental Deficits in Toddlers Exposed to Cocaine Before Birth

Download PDF Version What is PDF?

Robert Mathias

Robert Mathias is a Staff Writer for NIDA NOTES.

Source: NIDA NOTES, Vol. 17, No. 5, January, 2003

Public Domain

Table of Contents (TOC)

Article: Study Finds Significant Mental Deficits in Toddlers Exposed to Cocaine Before BirthReferences

Since the mid-1980s, up to 1 million children born in the United States are estimated to have been exposed to cocaine in the womb. Determining cocaine’s impact on these children’s development has been difficult because there often are other possible explanations for physical and mental problems the children may have, such as the mother’s use of other substances during pregnancy and poor prenatal care. Now, a NIDA-supported study that was able to separate the effects of cocaine from those of many other such factors has found that children born to poor, urban women who used cocaine throughout pregnancy were nearly twice as likely as children with similar backgrounds but no prenatal cocaine exposure to have significant cognitive deficits during their first 2 years of life.

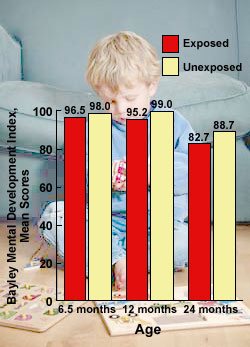

Mental Development Scores For Prenatally Cocaine-Exposed and Unexposed High-Risk Children

Tests of mental development at 6.5, 12, and 24 months showed average scores of cocaine-exposed and unexposed children from comparable backgrounds were below the normative score of 100 for children in the general population. At age 2, cocaine-exposed children did significantly poorer in mental development than children in the comparison group.

The study, led by Dr. Lynn Singer of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, is the first to show a clear association between prenatal cocaine exposure and cognitive impairment in 2-year-olds. "Since cognitive performance at this age is indicative of later performance, these children may continue to have learning difficulties that need to be addressed when they reach school age," Dr. Singer says.

"The findings of this well-controlled study make an important contribution to a growing body of knowledge about the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure that may help us to identify those exposed children who are at increased risk of developmental harm," says Dr. Vince Smeriglio of NIDA’s Center on AIDS and Other Medical Consequences of Drug Abuse. Previous findings from other NIDA-supported studies that have been following cocaine-exposed children from birth have produced conflicting results about cocaine’s impact on developmental outcomes at this age, he notes. "Comparing and contrasting the circumstances in this study with those found in other studies of cocaine-exposed children may enable us to identify specific biological and environmental factors that increase or reduce the developmental risk from cocaine exposure," Dr. Smeriglio says.

The study followed a group of 415 infants born at a large urban teaching hospital from 1994 through 1996 to mothers from low socio-economic backgrounds who had been identified by the hospital staff as being at high risk of drug abuse. Women who participated in the study were given urine tests for drug use immediately before or after delivery and interviewed shortly after they gave birth to produce estimates of the type, frequency, and amounts of drugs they had used during pregnancy. Each baby’s first stool, known as meconium, also was analyzed for the presence of cocaine and its metabolites to help establish the level of drug exposure. Of the 415 babies in the study, 218 had been exposed to cocaine and 197 had not. Both groups of infants also had been exposed to tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana during pregnancy.

Researchers measured the children’s developmental progress

at 6.5, 12, and 24 months of age with the Bayley Scales

of Infant Mental and Motor Development. Motor tests assessed

the infants’ ability to control and coordinate their movements.

Mental tests assessed language, memory, and ability to solve

problems at 12 and 24 months. For example, children were

asked to describe objects in pictures, remember where an

object had been hidden, and put shaped objects into the

correct spaces cut out on form boards.

Researchers measured the children’s developmental progress

at 6.5, 12, and 24 months of age with the Bayley Scales

of Infant Mental and Motor Development. Motor tests assessed

the infants’ ability to control and coordinate their movements.

Mental tests assessed language, memory, and ability to solve

problems at 12 and 24 months. For example, children were

asked to describe objects in pictures, remember where an

object had been hidden, and put shaped objects into the

correct spaces cut out on form boards.

To isolate cocaine’s effect, researchers adjusted test results for the effect of other risk factors, such as other drugs used during pregnancy; characteristics of biological mothers and alternative caregivers; the infants’ head size, weight, length, and gestational age at birth; and the quality of their postnatal home environments. The analysis showed that while prenatal cocaine exposure had not affected the infants’ motor development, it was clearly linked to significant deficits in their cognitive performance at age 2. Cocaine-exposed children scored 6 points lower on the Mental Development Index (MDI), averaging 82.7 percent compared to 88.7 percent for unexposed children and an average general population score of 100. Other findings include the following:

From 6.5 to 24 months, MDI scores declined for both groups, but cocaine-exposed children had a greater decline -- 14 points compared to a 9-point decline for unexposed children.

Almost 14 percent (13.7 percent) of cocaine-exposed children had scores in the mental retardation range, below 70 on the MDI, nearly twice the 7.1-percent rate found in the unexposed children and almost five times the rate (about 2.8 percent) expected in the general population.

Nearly 38 percent (37.8 percent) of cocaine-exposed children had developmental delays requiring remedial intervention, nearly double the 20.9 percent rate for unexposed children.

The study found that other influences, including the mother’s intelligence scores and educational level, exposure to other substances, and the quality of the postnatal home environment, also played significant roles in poor outcomes for cocaine-exposed children. "However, after controlling for these factors in our analysis, we found that cocaine still has a harmful effect on cognitive performance," Dr. Singer says. Additional support for this conclusion comes from mothers’ self-reports and biological data from mothers and infants that established a direct link between cocaine dose and toddlers’ cognitive performance. These data showed that children of mothers who used more cocaine and used it more frequently during pregnancy performed worse on the MDI than children of mothers who used less of the drug.

"The only risk factor we couldn’t completely control for is the effect of other drugs used during pregnancy," Dr. Singer says, "because it is nearly impossible to find children who have been exposed only to cocaine." The study partially adjusted for this influence by including children who had been heavily exposed to alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana in both groups. "Animal studies suggest there are possible synergistic effects of these drugs in combination, and the study may not have been large enough to control for these effects," she notes.

"We believe that cocaine exposure is a neurologic risk

factor that may take a poor child who has a lower IQ potential

because of maternal and other risk factors and push him

or her over the edge to mental retardation," Dr. Singer

says. For example, average IQ scores for both cocaine-exposed

and unexposed toddlers in the study were well below the

average score for the general population. "In effect, cocaine

lowered the range of IQ scores and that means more children

may require early stimulation and educational programs," she

says.

"We believe that cocaine exposure is a neurologic risk

factor that may take a poor child who has a lower IQ potential

because of maternal and other risk factors and push him

or her over the edge to mental retardation," Dr. Singer

says. For example, average IQ scores for both cocaine-exposed

and unexposed toddlers in the study were well below the

average score for the general population. "In effect, cocaine

lowered the range of IQ scores and that means more children

may require early stimulation and educational programs," she

says.

"While many children in this study may require special educational services when they enter school, it is important not to assume that the findings from a single study, with its unique characteristics, necessarily apply to all cocaine-exposed children," cautions NIDA’s Dr. Smeriglio. Ultimately, NIDA’s extensive portfolio of research on groups of cocaine-exposed children being raised in a variety of settings should provide detailed information about mother, child, environment, and drug-use characteristics that can be used to develop interventions that reduce risk of harm and guide clinical care for cocaine-exposed children.

Singer, L.T., et al. Cognitive and motor outcomes of cocaine-exposed infants. JAMA 287(15):1952-1960, 2002.