Research Report Series: Heroin Abuse and Addiction

Download PDF Version What is PDF?

Source: NIDA Research Report Series: Heroin Abuse and Addiction, NIH Publication No. 05-4165, Printed October 1997, Reprinted September, 2000, Revised May 2005.

Public Domain

Table of Contents (TOC)

From the DirectorChapter 1: What is heroin?

Chapter 2: What is the scope of heroin use in the United States?

Chapter 3: How is heroin used?

Chapter 4: What are the immediate (short-term) effects of heroin use?

Chapter 5: What are the long-term effects of heroin use?

Chapter 6: What are the medical complications of chronic heroin use?

Chapter 7: How does heroin abuse affect pregnant women?

Chapter 8: Why are heroin users at special risk for contracting HIV/AIDS and hepatitis B and C?

Chapter 9: What are the treatments for heroin addiction?

Chapter 10: What are the opioid analogs and their dangers?

Glossary

References

Heroin is a highly addictive drug, and its abuse has repercussions that extend far beyond the individual user. The medical and social consequences of drug abuse - HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, fetal effects, crime, violence, and disruptions in family, workplace, and educational environments - have a devastating impact on society and cost billions of dollars each year.

Although heroin abuse has trended downward during the past several years, its prevalence is still higher than in the early 1990s. These relatively high rates of abuse, especially among school-age youth, and the glamorization of heroin in music and films make it imperative that the public has the latest scientific information on this topic. Heroin also is increasing in purity and decreasing in price, which makes it an attractive option for young people.

Although heroin abuse has trended downward during the past several years, its prevalence is still higher than in the early 1990s. These relatively high rates of abuse, especially among school-age youth, and the glamorization of heroin in music and films make it imperative that the public has the latest scientific information on this topic. Heroin also is increasing in purity and decreasing in price, which makes it an attractive option for young people.

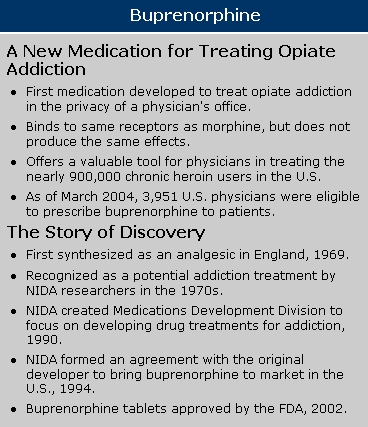

Like many other chronic diseases, addiction can be treated. Fortunately, the availability of treatments to manage opiate addiction and the promise from research of new and effective behavioral and pharmacological therapies provides hope for individuals who suffer from addiction and for those around them. For example, buprenorphine, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002, provides a less addictive alternative to methadone maintenance, reduces cravings with only mild withdrawal symptoms, and can be prescribed in the privacy of a doctor’s office.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has developed this publication to provide an overview of the state of heroin abuse and addiction. We hope this compilation of scientific information on heroin will help to inform readers about the harmful effects of heroin abuse and addiction as well as assist in prevention and treatment efforts.

Nora D.Volkow, M.D.

Director

National Institute on Drug Abuse

Heroin is an illegal, highly addictive drug. It is both the most abused and the most rapidly acting of the opiates. Heroin is processed from morphine, a naturally occurring substance extracted from the seed pod of certain varieties of poppy plants. It is typically sold as a white or brownish powder or as the black sticky substance known on the streets as "black tar heroin." Although purer heroin is becoming more common, most street heroin is "cut" with other drugs or with substances such as sugar, starch, powdered milk, or quinine. Street heroin can also be cut with strychnine or other poisons. Because heroin abusers do not know the actual strength of the drug or its true contents, they are at risk of overdose or death. Heroin also poses special problems because of the transmission of HIV and other diseases that can occur from sharing needles or other injection equipment.

According to the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which may actually underestimate illicit opiate (heroin) use, an estimated 3.7 million people had used heroin at some time in their lives, and over 119,000 of them reported using it within the month preceding the survey. An estimated 314,000 Americans used heroin in the past year, and the group that represented the highest number of those users were 26 or older. The survey reported that, from 1995 through 2002, the annual number of new heroin users ranged from 121,000 to 164,000. During this period, most new users were age 18 or older (on average, 75 percent) and most were male. In 2003, 57.4 percent of past year heroin users were classified with dependence on or abuse of heroin, and an estimated 281,000 persons received treatment for heroin abuse.

According to the Monitoring the Future survey, NIDA’s nationwide annual survey of drug use among the Nation’s 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-graders, heroin use remained stable from 2003 to 2004. Lifetime heroin use measured 1.6 percent among 8th-graders and 1.5 percent among 10th- and 12th-graders.

The 2002 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN), which collects data on drug-related hospital emergency department (ED) episodes from 21 metropolitan areas, reported that in 2002, heroin-related ED episodes numbered 93,519.

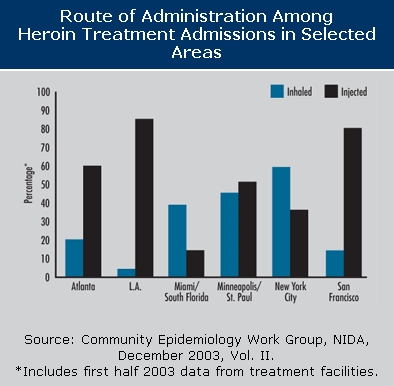

NIDA’s Community Epidemiology Work Group (CEWG) , which provides information about the nature and patterns of drug use in 21 areas, reported in its December 2003 publication that heroin was mentioned as the primary drug of abuse for large portions of drug abuse treatment admissions in Baltimore, Boston, Detroit, Los Angeles, Newark, New York, and San Francisco.

Heroin is usually injected, sniffed/snorted, or smoked. Typically, a heroin abuser may inject up to four times a day. Intravenous injection provides the greatest intensity and most rapid onset of euphoria (7 to 8 seconds), while intramuscular injection produces a relatively slow onset of euphoria (5 to 8 minutes). When heroin is sniffed or smoked, peak effects are usually felt within 10 to 15 minutes. NIDA researchers have confirmed that all forms of heroin administration are addictive.

Injection continues to be the predominant method of heroin use among addicted users seeking treatment; in many CEWG areas, heroin injection is reportedly on the rise, while heroin inhalation is declining. However, certain groups, such as White suburbanites in the Denver area, report smoking or inhaling heroin because they believe that these routes of administration are less likely to lead to addiction.

With the shift in heroin abuse patterns comes an even more diverse group of users. In recent years, the availability of higher purity heroin (which is more suitable for inhalation) and the decreases in prices reported in many areas have increased the appeal of heroin for new users who are reluctant to inject. Heroin has also been appearing in more affluent communities.

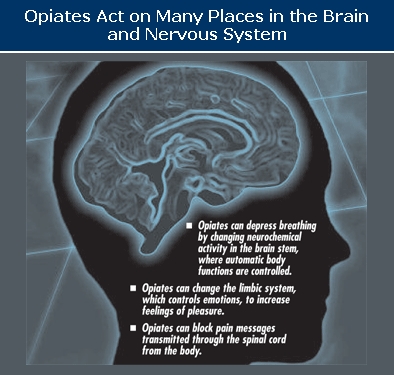

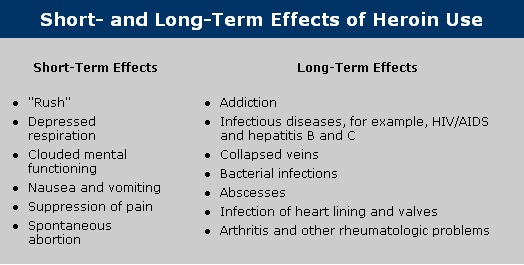

Soon after injection (or inhalation), heroin crosses the blood-brain barrier. In the brain, heroin is converted to morphine and binds rapidly to opioid receptors. Abusers typically report feeling a surge of pleasurable sensation, a "rush." The intensity of the rush is a function of how much drug is taken and how rapidly the drug enters the brain and binds to the natural opioid receptors. Heroin is particularly addictive because it enters the brain so rapidly. With heroin, the rush is usually accompanied by a warm flushing of the skin, dry mouth, and a heavy feeling in the extremities, which may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and severe itching.

After the initial effects, abusers usually will be drowsy for several hours. Mental function is clouded by heroin’s effect on the central nervous system. Cardiac function slows. Breathing is also severely slowed, sometimes to the point of death. Heroin overdose is a particular risk on the street, where the amount and purity of the drug cannot be accurately known.

One of the most detrimental long-term effects of heroin is addiction itself.

Addiction is a chronic, relapsing disease, characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, and by neurochemical and molecular changes in the brain. Heroin also produces profound degrees of tolerance and physical dependence, which are also powerful motivating factors for compulsive use and abuse. As with abusers of any addictive drug, heroin abusers gradually spend more and more time and energy obtaining and using the drug. Once they are addicted, the heroin abusers’ primary purpose in life becomes seeking and using drugs. The drugs literally change their brains and their behavior.

Physical dependence develops with higher doses of the drug. With physical dependence, the body adapts to the presence of the drug and withdrawal symptoms occur if use is reduced abruptly. Withdrawal may occur within a few hours after the last time the drug is taken. Symptoms of withdrawal include restlessness, muscle and bone pain, insomnia, diarrhea, vomiting, cold flashes with goose bumps ("cold turkey"), and leg movements. Major withdrawal symptoms peak between 24 and 48 hours after the last dose of heroin and subside after about a week. However, some people have shown persistent withdrawal signs for many months. Heroin withdrawal is never fatal to otherwise healthy adults, but it can cause death to the fetus of a pregnant addict.

At some point during continuous heroin use, a person can become addicted to the drug. Sometimes addicted individuals will endure many of the withdrawal symptoms to reduce their tolerance for the drug so that they can again experience the rush.

Physical dependence and the emergence of withdrawal symptoms were once believed to be the key features of heroin addiction. We now know this may not be the case entirely, since craving and relapse can occur weeks and months after withdrawal symptoms are long gone. We also know that patients with chronic pain who need opiates to function (sometimes over extended periods) have few if any problems leaving opiates after their pain is resolved by other means. This may be because the patient in pain is simply seeking relief of pain and not the rush sought by the addict.

Medical consequences of chronic heroin injection use include scarred and/or collapsed veins, bacterial infections of the blood vessels and heart valves, abscesses (boils) and other soft-tissue infections, and liver or kidney disease. Lung complications (including various types of pneumonia and tuberculosis) may result from the poor health condition of the abuser as well as from heroin’s depressing effects on respiration. Many of the additives in street heroin may include substances that do not readily dissolve and result in clogging the blood vessels that lead to the lungs, liver, kidneys, or brain. This can cause infection or even death of small patches of cells in vital organs. Immune reactions to these or other contaminants can cause arthritis or other rheumatologic problems.

Of course, sharing of injection equipment or fluids can lead to some of the most severe consequences of heroin abuse-infections with hepatitis B and C, HIV, and a host of other blood-borne viruses, which drug abusers can then pass on to their sexual partners and children.

Heroin abuse during pregnancy and its many associated environmental factors (e.g., lack of prenatal care) have been associated with adverse consequences including low birth weight, an important risk factor for later developmental delay. Methadone maintenance combined with prenatal care and a comprehensive drug treatment program can improve many of the detrimental maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with untreated heroin abuse, although infants exposed to methadone during pregnancy typically require treatment for withdrawal symptoms. In the United States, several studies have found buprenorphine to be equally effective and as safe as methadone in the adult outpatient treatment of opioid dependence. Given this efficacy among adults, current studies are attempting to establish the safety and effectiveness of buprenorphine in opioid-dependent pregnant women. For women who do not want or are not able to receive pharmacotherapy for their heroin addiction, detoxification from opiates during pregnancy can be accomplished with relative safety, although the likelihood of relapse to heroin use should be considered.

Heroin abuse during pregnancy and its many associated environmental factors (e.g., lack of prenatal care) have been associated with adverse consequences including low birth weight, an important risk factor for later developmental delay. Methadone maintenance combined with prenatal care and a comprehensive drug treatment program can improve many of the detrimental maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with untreated heroin abuse, although infants exposed to methadone during pregnancy typically require treatment for withdrawal symptoms. In the United States, several studies have found buprenorphine to be equally effective and as safe as methadone in the adult outpatient treatment of opioid dependence. Given this efficacy among adults, current studies are attempting to establish the safety and effectiveness of buprenorphine in opioid-dependent pregnant women. For women who do not want or are not able to receive pharmacotherapy for their heroin addiction, detoxification from opiates during pregnancy can be accomplished with relative safety, although the likelihood of relapse to heroin use should be considered.

Heroin users are at risk for contracting HIV, hepatitis C (HCV), and other infectious diseases, through sharing and reuse of syringes and injection paraphernalia that have been used by infected individuals, or through unprotected sexual contact with an infected person. Injection drug users (IDUs) represent the highest risk group for acquiring HCV infection; an estimated 70 to 80 percent of the 35,000 new HCV infections occurring in the United States each year are among IDUs.

NIDA-funded research has found that drug abusers can change the behaviors that put them at risk for contracting HIV through drug abuse treatment, prevention, and community-based outreach programs. They can eliminate drug use, drug-related risk behaviors such as needle sharing, unsafe sexual practices, and, in turn, the risk of exposure to HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases. Drug abuse prevention and treatment are highly effective in preventing the spread of HIV.

A variety of effective treatments are available for heroin addiction. Treatment tends to be more effective when heroin abuse is identified early. The treatments that follow vary depending on the individual, but methadone, a synthetic opiate that blocks the effects of heroin and eliminates withdrawal symptoms, has a proven record of success for people addicted to heroin. Other pharmaceutical approaches, such as buprenorphine, and many behavioral therapies also are used for treating heroin addiction. Buprenorphine is a recent addition to the array of medications now available for treating addiction to heroin and other opiates. This medication is different from methadone in that it offers less risk of addiction and can be prescribed in the privacy of a doctor’s office. Buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone) is a combination drug product formulated to minimize abuse.

Detoxification

Detoxification programs aim to achieve safe and humane withdrawal from opiates by minimizing the severity of withdrawal symptoms and other medical complications. The primary objective of detoxification is to relieve withdrawal symptoms while patients adjust to a drug-free state. Not in itself a treatment for addiction, detoxification is a useful step only when it leads into long-term treatment that is either drug-free (residential or outpatient) or uses medications as part of the treatment. The best documented drug-free treatments are the therapeutic community residential programs lasting 3 to 6 months.

Opiate withdrawal is rarely fatal. It is characterized by acute withdrawal symptoms which peak 48 to 72 hours after the last opiate dose and disappear within 7 to 10 days, to be followed by a longer term abstinence syndrome of general malaise and opioid craving.

Methadone programs

Methadone treatment has been used for more than 30 years to effectively and safely treat opioid addiction. Properly prescribed methadone is not intoxicating or sedating, and its effects do not interfere with ordinary activities such as driving a car. The medication is taken orally and it suppresses narcotic withdrawal for 24 to 36 hours. Patients are able to perceive pain and have emotional reactions. Most important, methadone relieves the craving associated with heroin addiction; craving is a major reason for relapse. Among methadone patients, it has been found that normal street doses of heroin are ineffective at producing euphoria, thus making the use of heroin more easily extinguishable.

Methadone’s effects last four to six times as long as those of heroin, so people in treatment need to take it only once a day. Also, methadone is medically safe even when used continuously for 10 years or more. Combined with behavioral therapies or counseling and other supportive services, methadone enables patients to stop using heroin (and other opiates) and return to more stable and productive lives. Methadone dosages must be carefully monitored in patients who are receiving antiviral therapy for HIV infection, to avoid potential medication interactions.

Buprenorphine and other medications

Buprenorphine is a particularly attractive treatment for heroin addiction because, compared with other medications, such as methadone, it causes weaker opiate effects and is less likely to cause overdose problems. Buprenorphine also produces a lower level of physical dependence, so patients who discontinue the medication generally have fewer withdrawal symptoms than do those who stop taking methadone. Because of these advantages, buprenorphine may be appropriate for use in a wider variety of treatment settings than the currently available medications. Several other medications with potential for treating heroin overdose or addiction are currently under investigation by NIDA.

In addition to methadone and buprenorphine, other drugs aimed at reducing the severity of the withdrawal symptoms can be prescribed. Clonidine is of some benefit but its use is limited due to side effects of sedation and hypotension. Lofexidine, a centrally acting alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, was launched in 1992 specifically for symptomatic relief in patients undergoing opiate withdrawal. Naloxone and naltrexone are medications that also block the effects of morphine, heroin, and other opiates. As antagonists, they are especially useful as antidotes. Naltrexone has long-lasting effects, ranging from 1 to 3 days, depending on the dose. Naltrexone blocks the pleasurable effects of heroin and is useful in treating some highly motivated individuals. Naltrexone has also been found to be successful in preventing relapse by former opiate addicts released from prison on probation.

Behavioral therapies

Although behavioral and pharmacologic treatments can be extremely useful when employed alone, science has taught us that integrating both types of treatments will ultimately be the most effective approach. There are many effective behavioral treatments available for heroin addiction. These can include residential and outpatient approaches. An important task is to match the best treatment approach to meet the particular needs of the patient. Moreover, several new behavioral therapies, such as contingency management therapy and cognitive-behavioral interventions, show particular promise as treatments for heroin addiction. Contingency management therapy uses a voucher-based system, where patients earn "points" based on negative drug tests, which they can exchange for items that encourage healthy living. Cognitive-behavioral interventions are designed to help modify the patient’s thinking, expectancies, and behaviors and to increase skills in coping with various life stressors. Both behavioral and pharmacological treatments help to restore a degree of normalcy to brain function and behavior, with increased employment rates and lower risk of HIV and other diseases and criminal behavior.

Drug analogs are chemical compounds that are similar

to other drugs in their effects but differ

slightly in their chemical structure.

Some analogs are produced by pharmaceutical companies

for legitimate medical reasons. Other analogs, sometimes

referred to as "designer" drugs,

can be produced in illegal laboratories

and are often more dangerous and potent

than the original drug. Two of the most commonly

known opioid analogs are fentanyl and meperidine

(marketed under the brand name Demerol, for example).

Drug analogs are chemical compounds that are similar

to other drugs in their effects but differ

slightly in their chemical structure.

Some analogs are produced by pharmaceutical companies

for legitimate medical reasons. Other analogs, sometimes

referred to as "designer" drugs,

can be produced in illegal laboratories

and are often more dangerous and potent

than the original drug. Two of the most commonly

known opioid analogs are fentanyl and meperidine

(marketed under the brand name Demerol, for example).

Fentanyl was introduced in 1968 by a Belgian pharmaceutical company as a synthetic narcotic to be used as an analgesic in surgical procedures because of its minimal effects on the heart. Fentanyl is particularly dangerous because it is 50 times more potent than heroin and can rapidly stop respiration. This is not a problem during surgical procedures because machines are used to help patients breathe.On the street, however, users have been found dead with the needle used to inject the drug still in his or her arm.

Addiction: A chronic, relapsing disease, characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use and by neurochemical and molecular changes in the brain.

Agonist: A chemical compound that mimics the action of a natural neurotransmitter to produce a biological response.

Analog: A chemical compound that is similar to another drug in its effects but differs slightly in its chemical structure.

Antagonist: A drug that counteracts or blocks the effects of another drug.

Buprenorphine: A mixed opiate agonist/antagonist medication for the treatment of heroin addiction.

Craving: A powerful, often uncontrollable desire for drugs.

Detoxification: A process of allowing the body to rid itself of a drug while managing the symptoms of withdrawal; often the first step in a drug treatment program.

Fentanyl: A medically useful opioid analog that is 50 times more potent than heroin.

Meperidine: A medically approved opioid available under various brand names (e.g., Demerol).

Methadone: A long-acting synthetic medication shown to be effective in treating heroin addiction.

Physical dependence: An adaptive physiological state that occurs with regular drug use and results in a withdrawal syndrome when drug use is stopped; usually occurs with tolerance.

Rush: A surge of euphoric pleasure that rapidly follows administration of a drug.

Tolerance: A condition in which higher doses of a drug are required to produce the same effect as during initial use; often leads to physical dependence.

Withdrawal: A variety of symptoms that occur after use of an addictive drug is reduced or stopped.

Community Epidemiology Work Group. Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse, Vol. II, Proceedings of the Community Epidemiology Work Group , December 2003. NIH Pub. No. 04-5365. Bethesda, MD: NIDA, NIH, DHHS, 2004.

Dashe, J.S.; Jackson, G.L.; Olscher, D.A.; Zane, E.H.; and Wendel, G.D., Jr. Opioid detoxification in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 92(5):854-858, 1998.

Dole, V.P.; Nyswander, M.E.; and Kreek, M.J. Narcotic blockade. Arch Intern Med 118(4):304-309, 1966.

Goldstein, A. Heroin addiction: Neurology, pharmacology, and policy. J Psychoactive Drugs 23(2):123-133, 1991.

Hughes, P.H.; and Rieche, O. Heroin epidemics revisited. Epidemiol Rev 17(1):66-73, 1995.

Hulse, G.K.; Milne, E.; English, D.R.; and Holman, C.D.J. The relationship between maternal use of heroin and methadone and infant birth weight. Addiction 92(11):1571-1579, 1997.

Jansson, L.M.; Svikis, D.; Lee, J.; Paluzzi, P.; Rutigliano, P.; and Hackerman, F. Pregnancy and addiction; a comprehensive care model. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 13(4):321-329, 1996.

Jarvis, M.A.; and Schnoll, S.H. Methadone use during pregnancy. NIDA Research Monograph 149, 58-77, 1995.

Johnson, R.E.; Jones, H.E.; and Fischer, G. Use of buprenorphine in pregnancy: patient management and effects on neonate. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 70(2):S87-S101, 2003.

Jones, H.E. Practical Considerations for the Clinical Use of Buprenorphine. Science & Practice Perspectives 2(2):4-20, 2004.

Kornetsky, C. Action of opioid on the brain-reward system. In: Rapaka, R.S.; and Sorer, H.; eds. Discovery of Novel Opioid Medications . National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 147. NIH Pub. No. 95-3887. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print Off., 1991, pp. 32-52.

Kreek, M.J. Using methadone effectively: Achieving goals by application of laboratory, clinical, and evaluation research and by development of innovative programs. In: Pickens, R.; Leukefeld, C.; and Schuster, C.R.; eds. Improving Drug Abuse Treatment . National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 106. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1991, pp. 245-266.

Lewis, J.W.; and Walter, D. Buprenorphine: Background to its development as a treatment for opiate dependence. In: Blaine, J.D., ed. Buprenorphine: An Alternative for Opiate Dependence . National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 121. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM) 92-1912. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1992, pp. 5-11.

Luty, J.; Nikolaou, V.; and Bearn, J. Is opiate detoxification unsafe in pregnancy? J Subst Abuse Treat 24(4):363-367, 2003.

Maas, U.; Kattner, E.; Weingart-Jesse, B.; Schafer, A.; and Obladen, M. Infrequent neonatal opiate withdrawal following maternal methadone detoxification during pregnancy. J Perinat Med 18(2):111-118, 1990.

Mathias, R. NIDA survey provides first national data on drug abuse during pregnancy. NIDA NOTES 10:6-7, 1995.

Messinger, D.S.; Bauer, C.R.; Das, A.; Seifer, R.; Lester, B.M.; Lagasse, L.L.; Wright, L.L.; Shankaran, S.; Bada, H.S.; Smeriglio, V.L.; Langer, J.C.; Beeghly, M.; and Poole, W.K. The maternal lifestyle study: cognitive, motor, and behavioral outcomes of cocaine-exposed and opiate-exposed infants through three years of age. Pediatrics 113(6):1677-1685, 2004.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. "Heroin." NIDA Capsule . NIDA, 1986.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. IDUs and infectious diseases. NIDA NOTES 9:15, 1994.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the Future, National Results on Adolescent Drug Use, Overview of Key Findings 2004 . NIH Pub. No. 05-5726. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 2005.

Novick, D.M.; Richman, B.L.; Friedman, J.M.; Friedman, J.E.; Fried, C.; Wilson, J.P.; Townley, A.; and Kreek, M.J. The medical status of methadone maintained patients in treatment for 11-18 years. Drug and Alcohol Depend 33(3):235-245, 1993.

Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 04-3964. SAMHSA, 2004.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. Heroin Facts and Figures . Rockville, MD, 2004. Available at www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/drugfact/heroin/index.html.

Sobel, K. NIDA’s AIDS projects succeed in reaching drug addicts, changing high-risk behaviors. NIDA NOTES 6:25-27, 1991.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. Emergency Department Trends From the Drug Abuse Warning Network, Final Estimates 1995-2002. DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 63-3780. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2003.

Swan, N. Research demonstrates long-term benefits of methadone treatment. NIDA NOTES 9:1, 4-5, 1994.

Woods, J.H.; France, C.P.; and Winger, G.D. Behavioral pharmacology of buprenorphine: Issues relevant to its potential in treating drug abuse. In: Blain, J.D., ed. Buprenorphine: An Alternative for Opiate Dependence. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 121. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM) 92-1912. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1992, pp. 12-27.